Dorset's Forest Ranger School

Article by J. Patrick Boyer

Muskoka forests sustain wildlife, supply wood-product industries and attract visitors. Yet tourists once gazed upon Muskoka’s clearcut stump-and-slash scenery with the impression of an apocalyptic vision.

In the 1850s, when loggers began felling Muskoka’s forests, some crossed the Severn River from logged-out Simcoe County and others worked up the Algonquin dome’s watershed. Lumbering continued as an economic driver and political juggernaut.

Logging companies and sawmills employed thousands. Their owners became wealthy timber barons. Queen’s Park reveled at all the jobs and provincial revenues. As these were Crown lands, not private forests, Ontario’s forestry department exercised provincial jurisdiction over natural resources.

Departmental foresters measured out timber berths to auction for harvesting. They also monitored forest and mill operations to ensure stumpage fees were accurate and Crown royalties collected. Other staff gathered statistics to report on Ontario forestry operations.

Conservationists appealed to Queen’s Park for better forestry policies because all-out logging seemed on a par with forest fire devastation. More attention was needed for silviculture (care of forests) and dendrology (the study of trees), but Ontarians’ overarching concerns were forest fires and logging practices.

In 1882 Bracebridge’s Aubrey White, Muskoka’s Crown lands agent, became Ontario’s Deputy Minister of Lands and Forests. He took to Queen’s Park visceral understanding of the need to control fires and initiated a system of fire rangers and fire-observation towers. By 1885, more than three-dozen Lands and Forests rangers patrolled northern woods.

By the twentieth century, more people were using forests for different purposes. The commercial value of wooded areas for lumber and tourist lodgings soared. Besides logging, camping, hunting, fishing, waterways, and roads, the challenge was nature’s own handling of forests with fires and infestations. Because foresters and game wardens shouldered all these tasks, better training would make them more effective and benefit both the forests and Ontarians.

A 1906 Ontario royal commission concluded, “No doubt a great deal of work in forestry can be done in this province by the University of Toronto, provided it receives the co-operation and encouragement of the government.” The following year the university across the road from Queen’s Park created Canada’s first Faculty of Forestry.

In 1919, Ontario’s new Farmer-Labour government, ousting the old-line parties, initiated an Ontario Air Service for forestry operations and headquartered at Sault Ste Marie. By 1921, to get more forest management operations into the north, one of those planes tracked the Bobcaygeon colonization road into Muskoka north to Dorset. From above, forester Peter McEwen spotted an ideal location by St. Nora Lake, where soon the new Chief Fire Ranger station was built.

By 1940, the imperative of a northern location for the university’s outdoor teaching program led to use of a Haliburton boy’s camp on Boshkung Lake. In 1943 visionary forester Peter McEwen of Lands and Forests, who had foreseen St. Nora Lake’s potential, delivered a paper to the Canadian Society of Forest Engineers proposing Ontario establish a forest ranger school. The government acted immediately. McEwen would determine the school’s location, devise its curriculum and become its inaugural director.

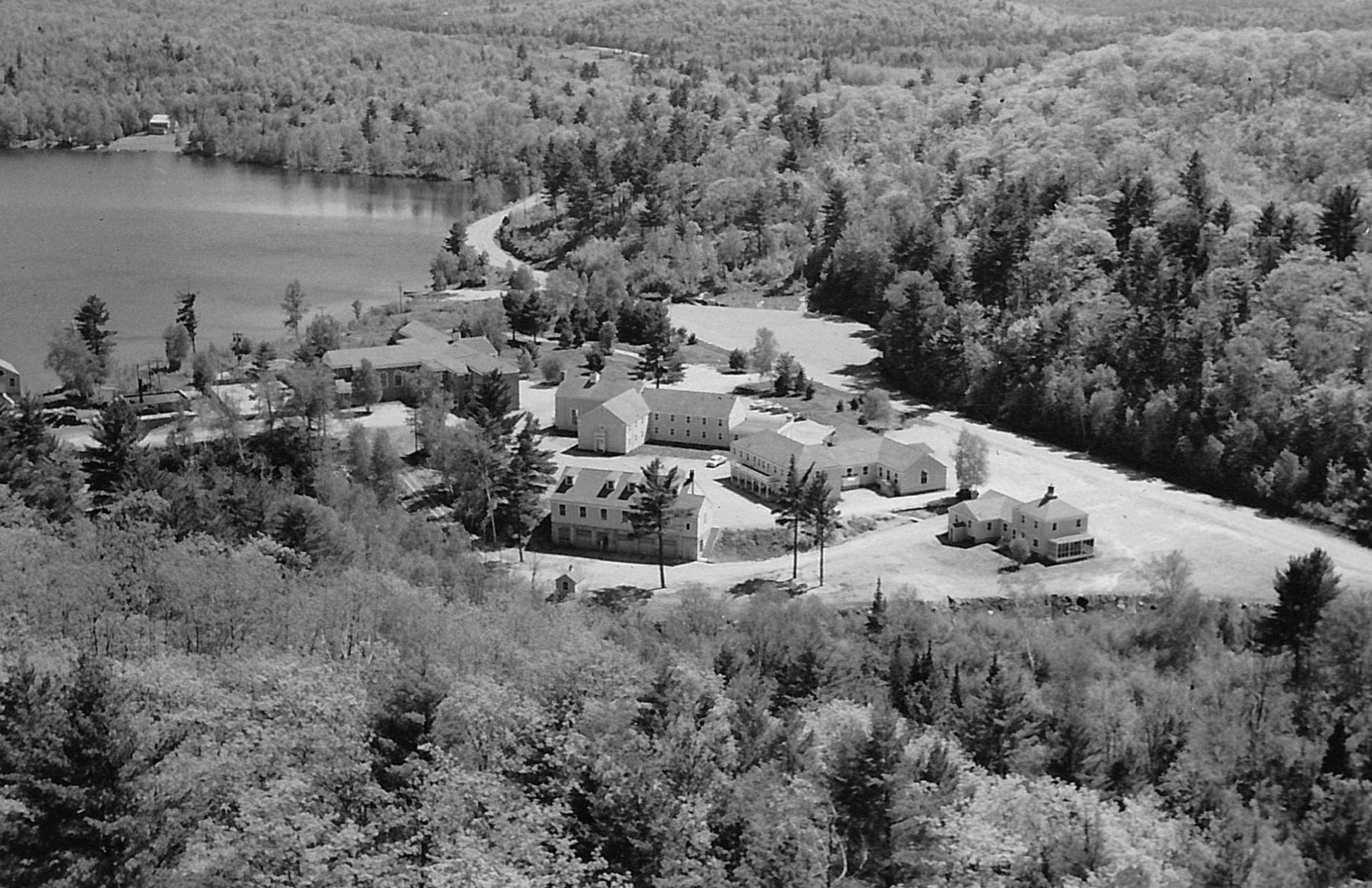

The forest ranger school, supplanting instruction at Boshkung, was established south of Dorset by the St. Nora Lake Fire Ranger headquarters. The campus was just barely in Haliburton County. Nearby Dorset’s main street straddles the Muskoka-Haliburton boundary. In Toronto, where it was all the same thing, “Dorset” became shorthand for the forester school.

In June 1944, Lands and Forests and University of Toronto formed a partnership. The government would erect all buildings, place a full-time ranger on site, hire a superintendent, and enroll students. The university would run undergrad and graduate courses, equip the facility with educational materials and equipment, manage the buildings and operate a “university forest.”

The mixed woodland, rich in wildlife, began as 2,000 acres west of St. Nora Lake, across the highway from the Fire Ranger headquarters. By the mid-1950s, the training and teaching forest would encompass 17,000 acres, including a corner of Muskoka’s Ridout Township.

Construction of the school, begun in 1944, continued to 1948. In autumn 1945, when the first 50 students arrived, the campus alongside Highway 35 was a work-in-progress, with classes held in tents. Students reached their classes through builders, moving machinery and stacked construction materials for what would become one of North America’s most prestigious forestry academies.

Previously, Ontario forestry training had been for Lands and Forests personnel. Now, to their mutual benefit, government foresters mixed with students enrolled in the University of Toronto’s forestry program. The blended stream received both classroom instruction and hands-on teaching in the university forest, which faculty also turned into a laboratory for experiments and longer-term observations.

Ontario’s Forest Ranger School institutionalized the campaign of conservationists and foresters to monitor and protect Ontario forests. From 1945 to 1966, the facility expanded, responding to new forester roles while upgrading methods of instruction.

In the 1940s, rangers wanting to upgrade their education were men 40-years or older employed by Lands and Forests having at least Grade 8. As the curriculum expanded and faculty mandates grew, what had begun as continuing education for Lands and Forests personnel and higher education for university students shifted to include post-war training for soldiers wanting work in public and private forestry. After that phase, the program morphed into a post-secondary option for younger and less-experienced high school graduates. Then women showed up for classes amidst the ranks of male foresters.

In the 1950s, one of the forestry students was George Long of Gravenhurst who liked outdoor life more than factory employment. In 1953, he left lab work at Gravenhurst’s Rubberset plant for a temporary job with Lands and Forests at Dorset. Earning $5.45 a day plus $35 a month for costs of living, Long enjoyed fresh air from spring to fall, having nothing to do with the Forestry School.

Next year, Long landed timber clerk work in Lands and Forests’ Parry Sound office. By 1957, his impressed supervisor suggested the department would pay Long’s salary while he studied at the Ranger School to qualify as a timber technician.

For classroom instruction, rows of desks faced a large blackboard on which instructors wrote in white chalk key points about lessons that rotated through geology and soil types, fish and wildlife, fire protection of forests, mathematics, tree types and characteristics, surveying, road building, and timber cruising.

Timber cruising, vital work for foresters, explains Long, “involves running a line into the bush for a mile or so, then measuring the girth of trees and calculating how many of each size stood in that sector, based on extensive sampling and measuring.” The forester “then calculated the area’s volume of harvestable wood,” data the government uses setting fees for the timber berth and lumber companies rely on when bidding for cutting rights. Hands-on instruction in cruising “required a full afternoon of teaching in the forest,” recalls Long.

By the 1960s, evolution became transformative. Entrance now required Grade 10 education. Graduating from Ontario’s Forest Ranger School was a prerequisite for anyone seeking outdoor work with Lands and Forests. More females were joining forestry classes. The field itself was expanding with other forestry schools operating in New Brunswick, Quebec, and Alberta.

In 1964, the forestry school was brought under Ontario’s Technical and Vocational Schools Act. The change qualified it for more government funding and students for government-backed loans but the tradeoff drew the school into Ontario’s mushrooming educational system.

Curriculum had been driven by new technology and forestry innovations. Forestry fundamentals focused on trees, care of forests, distinguishing all types of plants and wildlife, operational practicalities of surveying, drafting, mathematics and road locating, and familiarity with forest environments. But now structural revamping of Ontario’s educational apparatus and new policies at Queen’s Park shifted the school’s very foundations.

In 1966, the Forest Ranger School was renamed the Ontario Forestry Technical School. Two years later, its training curriculum was transferred from University of Toronto to Sir Sandford Fleming College at Peterborough, one of Ontario’s 21 emerging Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology and one of the province’s three College Institutes of Technology and Advanced Learning. The University of Toronto terminated its agreement with Lands and Forests. The next year, the university surrendered its Crown lease on the training forest at Dorset.

Radical revamping of Ontario post-secondary education altered forest worker education. In tandem, specific training was increasingly provided by forestry companies for their own employees.

“The government could neither afford nor justify the whole operation without the university’s involvement,” observed Carol Moffatt in Minden & Area magazine, “so the facility at Dorset was handed over to the Ministry of Education. The school reverted to its original role, offering short courses for Lands and Forests employees, adding some outdoor education courses.”

By the winter of 1969-70, it was even offering outdoor education classes to public schoolers. Grade 6 classes from Bracebridge Public School attended its five-day course that winter, staying in the foresters’ dormitory and eating in their cafeteria.

In 1974, another shift came when Premier Bill Davis redesignated the former Forest Ranger School the Leslie M. Frost Natural Resource Centre. It was a nod to the former premier and Haliburton MPP who oversaw creation of Ontario’s forestry school but the reality was the institution’s role had changed. The Frost Centre’s newly improvised purpose made use of a remnant facility whose mandate had evaporated.

Like other purpose-built complexes, the afterlife of Ontario’s Forest Ranger School entered a twilight zone. After the abrupt closure of the Frost Centre in 2004 as a cost-saving political move, the facility became an environmentally-focused private school until 2010. The property and its 21 buildings were severed from the university forest.

After several stumbles and dead ends, the facility was listed for sale in 2020. Multiple bids pushed the number high and the Ontario Public Service Employees Union’s cinched acquisition with $3.2 million in January 2021. OPSEU would revitalize the historic site as a training and vacation centre for members. Work began but stalled with OPSEU’s leadership crisis.

Whatever fate awaits the buildings and land at St. Nora Lake, Ontario’s unique Forest Ranger School, in its time and place, launched deeper understanding of precious woodlands and developed worthy steps to sustain healthy forests.